This post is an abridged version of our recent talk at BSides Chicago 2025. The slides can be found here: https://github.com/SecurityRiskAdvisors/public-assets/blob/main/BSides%20Chicago%202025/Pruning%20Garden%20Paths%20in%20AWS.pdf

In this blog, we will introduce a new graph-based tool for evaluating the security of AWS environments.

Background and Prior Art

When assessing the security of cloud environments, typically the types of checks you may want to perform are either static checks or relational checks. Static checks look at the current configuration of a resource in isolation and validate each configuration conforms to some best practice, such as those provided by CIS. Relational checks look for issues based on the relationship between multiple resources and are especially concerned about one resource’s ability to influence another resource(s). A static check may look to see if an EC2 instance is configured to allow the less-secure IMDSv1 whereas a relational check may look to see if a user has administrative rights over that instance. Both types of checks are necessary and complement one another.

Example graph of relationships between AWS databases and account.

Source: https://cartography-cncf.github.io/cartography/usage/tutorial.html

There have been several attempts to leverage graphs for AWS security. Notably:

- Cartography (https://cartography-cncf.github.io/cartography)

- awspx (https://github.com/WithSecureLabs/awspx/)

- Pmapper (https://github.com/nccgroup/PMapper/)

- Apeman (https://github.com/hotnops/apeman/)

- IAMhounddog (https://github.com/VirtueSecurity/IAMhounddog/)

Cartography being the most mature, battle-tested of these. When reviewing these tools, and others, to determine what the current state of the art was, we identified several common limitations across them that ultimately led us to develop our own tool. That’s not to say these tools were bad, just that they didn’t meet our needs.

The first limitation was around handling IAM permissions. Often, tools would take a naïve approach to evaluating IAM permissions, simply checking if a permission was in a principal’s identity policies without evaluating the larger context of those policies for restrictions like explicit denies.

The second limitation was around resource support. Tools would only support a small set of AWS resources (e.g. IAM roles, users). Additionally, they did not provide a mechanism for extending supported resources. To add new resource types, you’d essentially need to fork the project then modify the core code.

The third limitation was around analysis. The typical functionality would be to do data collection, perform analysis, then produce a finalized graph. Like the resource limitations, there was also not a meaningful way to extend analysis beyond forking the code.

Coming out of this review, our design goals for a new tool that would address these limitations and our workflow needs would:

- Map AWS attack paths

- Handle complex IAM permissions contexts

- Provide a mechanism to extend the resources and the analysis

- Keep relationships higher-signal and more intentional rather than polluting the graph with noisy relationships

- Support rapid, iterative analysis focused on a human being in the loop

The last point being the most important. An analyst should be able to perform some initial collection and analysis, get an understanding of the environment, then use that understanding to drive additional collection, analysis, and feature development.

AWS Attack Paths

Attack paths of interest in AWS mostly fall into one of four high-level categories.

The first is traditional privilege escalation. There are many permissions in IAM that are especially risky as they can allow for direct escalation of privileges. For example, permissions like iam:PutRolePolicy and iam:AttachRolePolicy allow a principal to manage the permissions of IAM roles by adding inline policies and attaching managed policies. A role with either of these permissions can potentially assign themselves administrative privileges (*:* access) if the permissions are not restricted.

The second category is action on objective related permissions. These are permissions that are not necessarily privileged in their own right but they allow an attacker to achieve some desired end goal, such as reading sensitive information from a data store.

The third category is for cross-account permissions. Using multiple AWS accounts is not uncommon and even recommended by AWS. As a result, resources may need to interact with resources in other accounts. Misconfigurations in cross-account mechanisms (e.g. resource policies) can create opportunities for exploitation paths spanning account boundaries.

The last category is service abuse. AWS services can interact in a customer account both as a service principal (e.g. <service>.amazonaws.com) and via an IAM role configured with a service trust in the trust policy. Trusting services to act within accounts opens the door for confused deputy attacks where an attacker induces the service principal to act in some unintended manner, abusing the privileges of that service.

For more details about traditional privilege escalation and service abuse, refer to our previous posts, respectively:

AWS IAM

Ultimately, AWS IAM underpins these abuse mechanisms. Being able to represent IAM permissions, of which there are many, in a graph is therefore especially important.

Example IAM policy that allows basic EC2 read

Looking at an example policy, a first attempt at mapping this into a graph might do it on a per-statement basis. Each policy contains one or more statements that define the allowed and disallowed actions. In the above example, the statement provides basic read access in EC2. A resulting path might look like:

Basic EC2 read path between two nodes

However, you’ll notice the policy contains two wildcards (“*”), one in the action and one in the resource. Should these be expanded and, if so, how should the expansion be handled? The action of ec2:Describe* can be expanded to almost 200 individual actions.

Example relationship between a policy and S3 object

Source: awspx (https://github.com/WithSecureLabs/awspx/)

And each of those actions may interact with different resource types, in some cases more than one type per action. Describing an instance would have a resource type of an instance whereas describing a volume would have a resource type of a volume. What’s more, each of these actions may have multiple associated condition keys that affect the resources. AWS is also frequently adding more services and actions, and you as a customer will be adding and removing resources. The wildcards will need to adjust to maintain parity with the environment.

Going back to the example policy, what if you were to add a second statement.

Adding a deny statement to the example policy

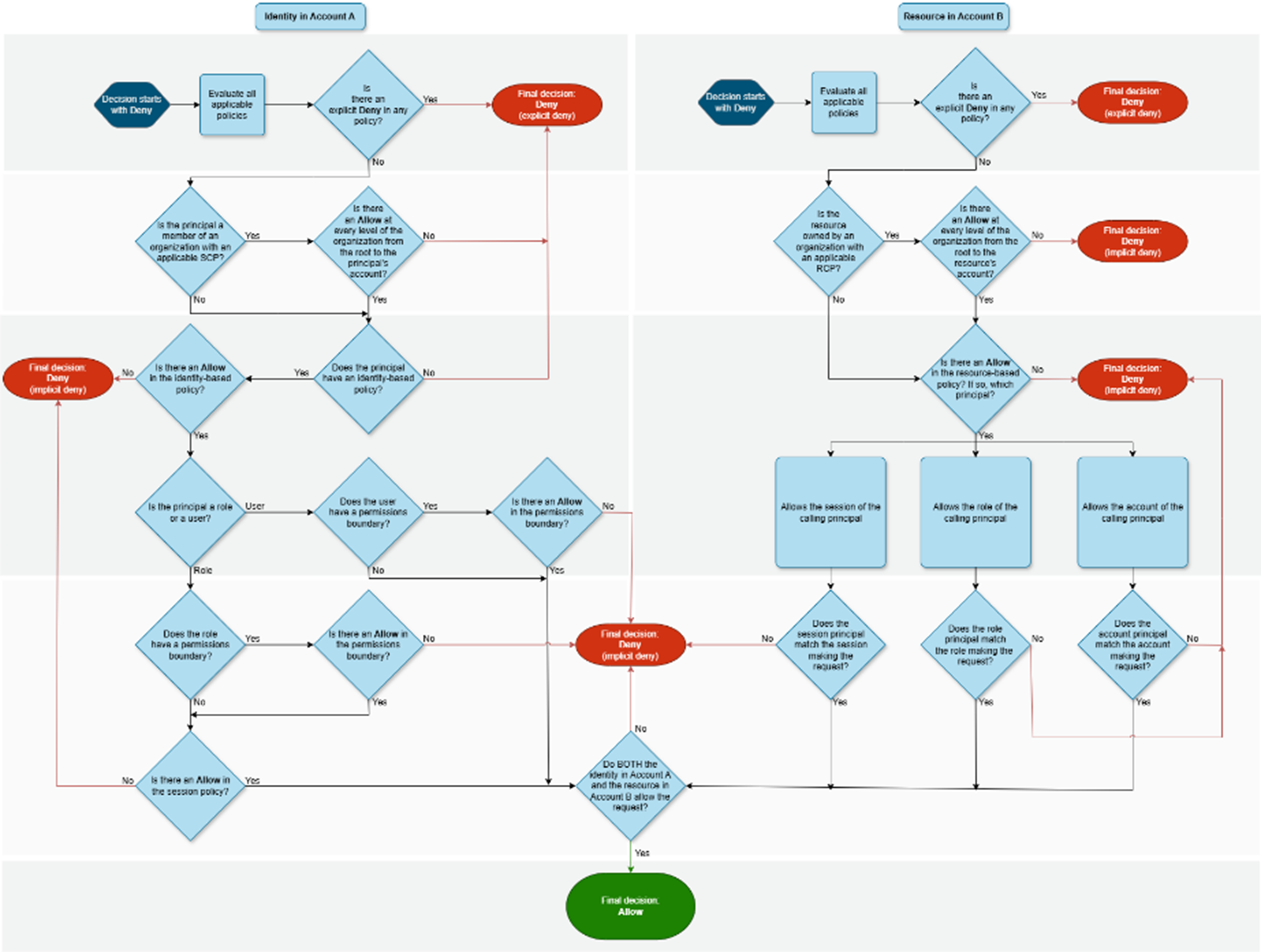

The policy now includes a deny statement for one of the ec2:Describe* actions. And beyond the individual policy level, there are other restrictions that could affect those actions. Restrictions such as service control and resource control policies that restrict actions at the account level, permissions boundaries that restrict actions at the principal level, and resource policies that restrict actions at the resource level all need to be considered.

AWS policy evaluation logic

These restrictions as well as wildcards, conditions, and resource types, among others, all affect how one might choose to represent the data in a graph.

Neph

Our tool, Neph, attempts to address the noted limitations in a novel way.

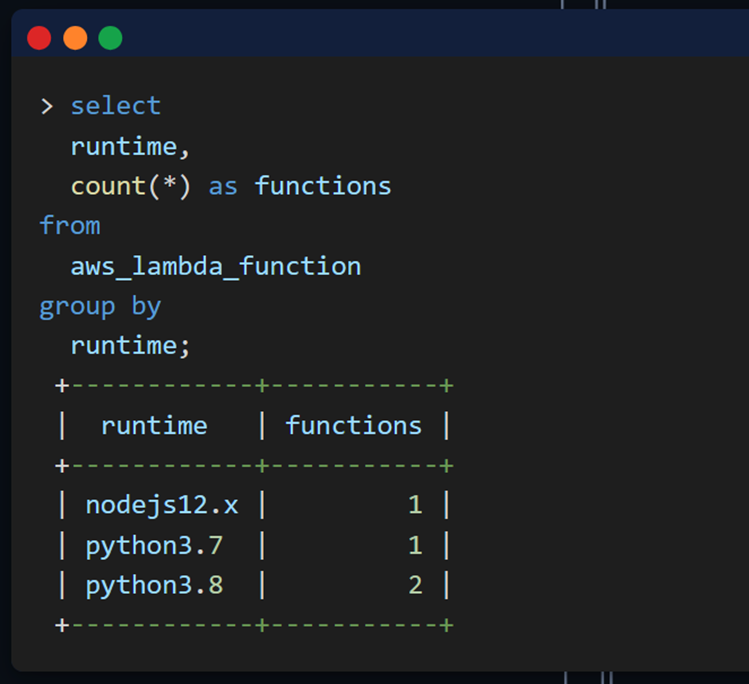

To address the limitation of supported resources, Neph uses Steampipe to act as the data collection engine. Steampipe is an open-source tool that provides a SQL interface for reading cloud data. Users can use SQL queries to retrieve their cloud resources and their configurations. For example, to summarize Lambda function runtimes, you can run a query like:

Steampipe querying AWS Lambda

Source: https://steampipe.io/

Steampipe also naturally handles multi-region and multi-account collection as well as error handling.

But the real power of Steampipe comes from its ability to host a PostgreSQL database interface. Because of this, you can query Steampipe data via JDBC (a Java standard for database clients), allowing you to interact with Steampipe from Neo4j, the graph database Neph uses. From Neo4j, you can initiate a SQL query in Steampipe. Then, Steampipe will query your cloud resources and return the data to Neo4j. Finally, Neo4j can persist the data into the graph. This allows for highly scalable resource collection without needing to explicitly build anything ourselves.

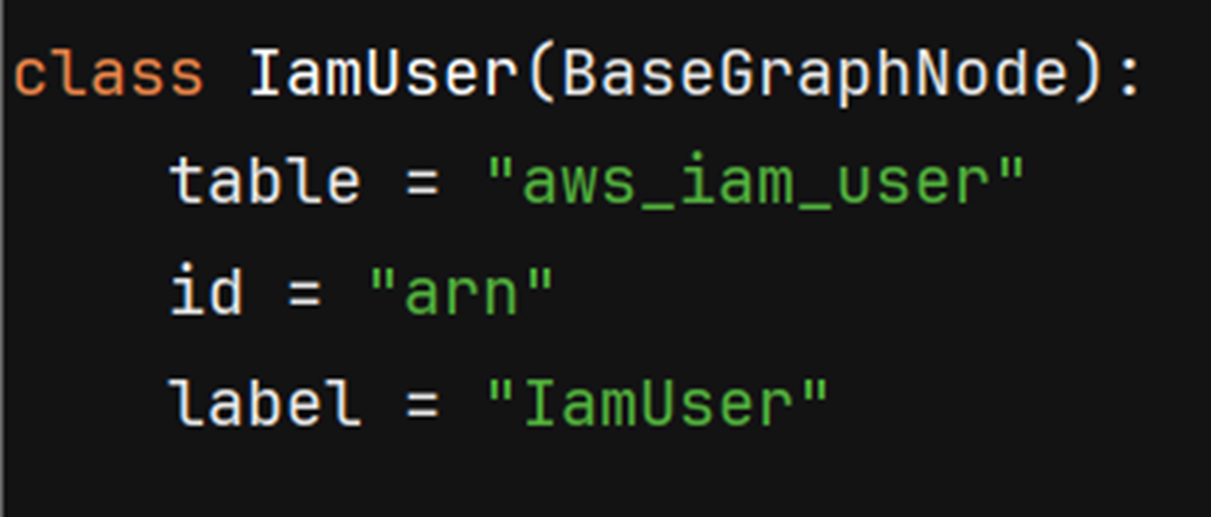

Users of Neph can ingest any of the resources supported by Steampipe by using its extensions functionality for adding new graph nodes.

Example Neph node definition

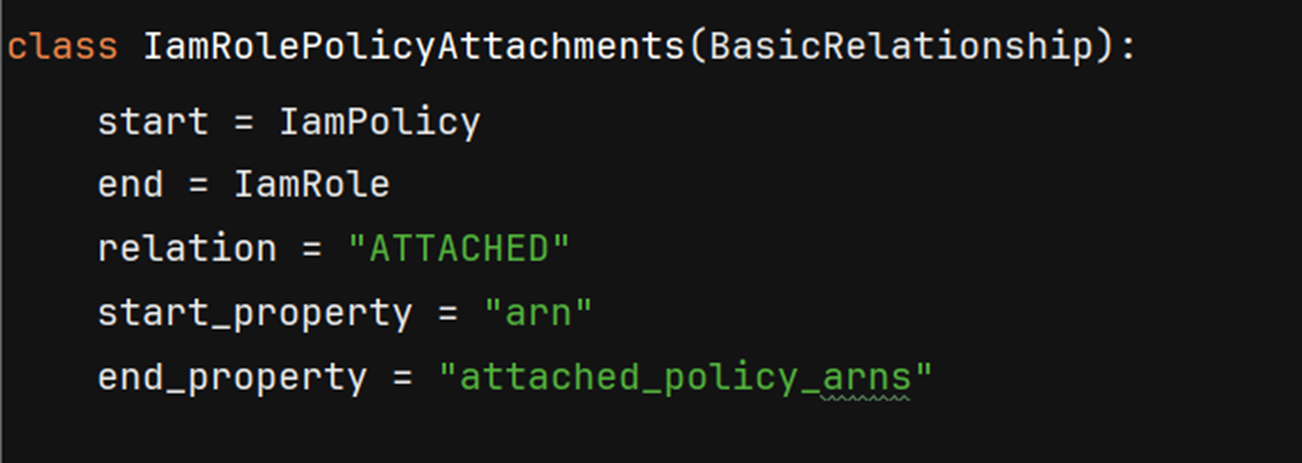

Example Neph relationship definition for relating IAM policies to roles

Example resulting relationship in the graph

Users can leverage both the prebuilt edge types that map nodes based on shared properties or provide their own mapping logic.

Separate from these base edges are another edge type called a “lead”. These edges are meant to signal to an operator that additional analysis may be required. For example, when evaluating a role trust policy, the policy can reference another principal so you can create an edge between the two resources. However, the conditions in the policy may mean the principal can’t assume the target role. A lead is a better fit for this. Seeing the lead, the operator then knows they need to verify if the assume role call would succeed (more on that below).

To address the limitation around IAM, Neph uses a local IAM policy simulator project. This project takes in any number of policies and a request detailing the action being performed, resources, conditions, etc, then returns whether or not the action is allowed and why. Since the relevant policy objects are stored in the graph, Neph can provide an abstraction on top of this functionality that determines if a principal can perform an action. It can also create edges based on the results of this simulation.

ssm:StartSession

Example: Traditional Privilege Escalation

This example walks through analyzing traditional privilege escalation using Neph.

As noted earlier, traditional privilege escalation opportunities arise when a principal is assigned one or more abusable permissions, such as iam:PutRolePolicy. But these permissions can be used legitimately. An administrator would be expected to have these permissions, especially if they manage IAM resources. How can you show risk for these permissions?

Schematically, you should look for instances where a principal without these privileges can get exposure to them. Essentially looking for an increase in privilege level. Breaking this down, you would first identify target roles that have an associated identity policy granting an abusable permission(s). The riskiest of these would be principals that can call the associated actions unconditionally (without policy conditions and without resource restrictions). You would then look for users/roles that do not have an abusable permission(s) in their identity policies but do have an assume role path to one of the target roles. This would indicate a low-privilege principal can assume a high-privilege role, thereby increasing their privilege level.

Using Neph to perform this analysis, you would:

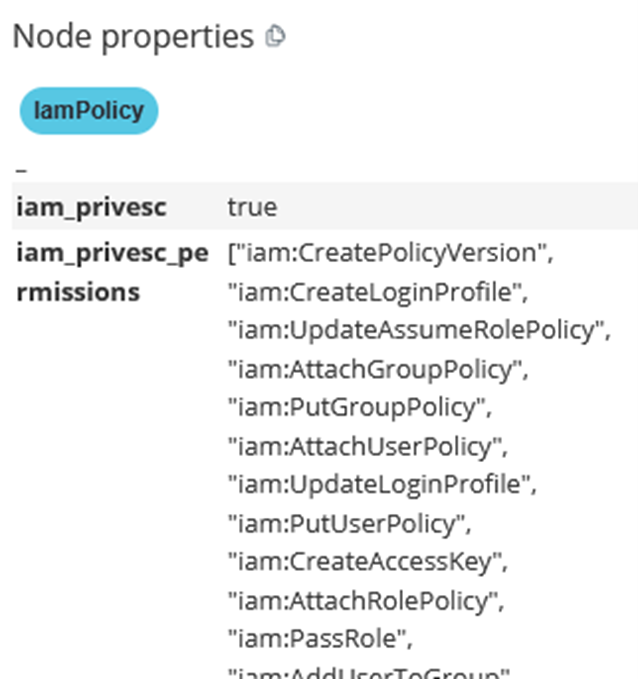

- Query for principals with attached policies where at least one policy has an abusable permission (filtering out

iam:PassRole, which is an abusable permission but has a much higher complexity level for exploitation)

MATCH p=(n)<-[:ATTACHED]-(m:IamPolicy|IamInlinePolicy)

WHERE toBoolean(m.iam_privesc) = TRUE

and not m.iam_privesc_permissions ='["iam:PassRole"]'

…

Example relationship (top) between a role and an attached policy containing an abusable permissions (bottom)

- Validate the principal can perform the abusable action unconditionally by simulating it against a wildcard resource

> neph sim --principal “<TARGET>” --action <ABUSABLE> --resource * …

- Query for principals with attached policies where none of the policies have an abusable permission

MATCH (z:IamRole|IamUser)

WHERE count{(z)<-[:ATTACHED]-(pol{iam_privesc:"true"})} = 0

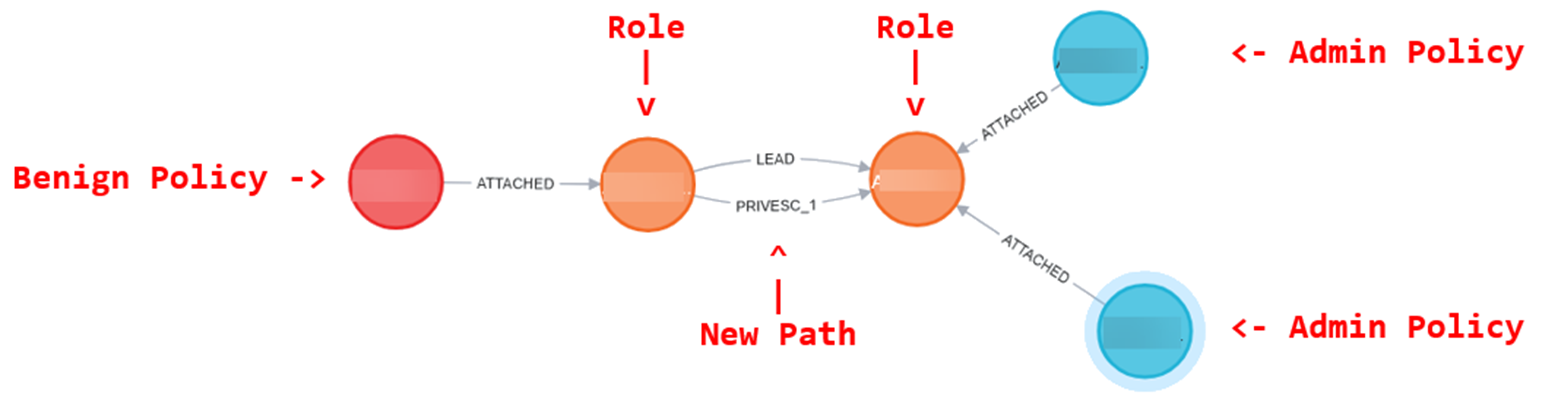

- Looks for paths starting with principals from step #3 and ending with principals from step #1

- Validate the low-privilege principal can assume the high-privilege role by simulating the

sts:AssumeRole call

> neph sim --principal “<SOURCE>” --action sts:AssumeRole --resource “<TARGET>” …

The final path looks like:

Example relationship (top) between a role and an attached policy containing an abusable permissions (bottom)

Closing

Neph is available now on our GitHub: https://github.com/SecurityRiskAdvisors/neph. Refer to the quick start guide for getting started. As a general caveat: Neph is still in active development and should be considered an alpha release.

If you have any questions or concerns, feel free to reach out to @2xxeformyshirt.