In an AWS customer account, resources like virtual machines and databases are typically created by user principals tied to that customer, such as a developer role or IAM user. In some circumstances however, AWS itself will create/interact with resources in a customer’s account on their behalf. The way in which it achieves this will change based on the service being used and the API method being called. At the time of writing, there are three notable mechanisms: 1) service and service-linked roles, 2) user impersonation, and 3) fully internal actions. Service and service-linked roles are traditional IAM roles configured to allow an AWS service to assume it. User impersonation is where the action is performed by AWS but by reusing the calling principal and its permissions. Fully internal actions are performed by AWS itself and bypass user permissions. In this blog, we will describe the mechanics of these actions and their relationship with standard authorization and auditing controls (e.g. IAM, CloudTrail).

Service(-linked) Roles

There are two types of service-related roles used by AWS services: service roles and service-linked roles (for the purposes of this blog, the collective is referred to as “service-related roles”). Service roles are standard IAM roles configured by the customer and have a trust policy allowing assumption by an AWS service(s). Service-linked roles have predefined permissions that cannot be modified by a customer. Whether to use a service role or a service-linked role will depend on the AWS service itself. Some services even support both service roles and service-linked roles, for example AWS Batch.

Both role types available for the Batch service

Some services do not support the use of IAM roles. Refer to AWS documentation for a full table of which services use roles: https://docs.aws.amazon.com/IAM/latest/UserGuide/reference_aws-services-that-work-with-iam.html

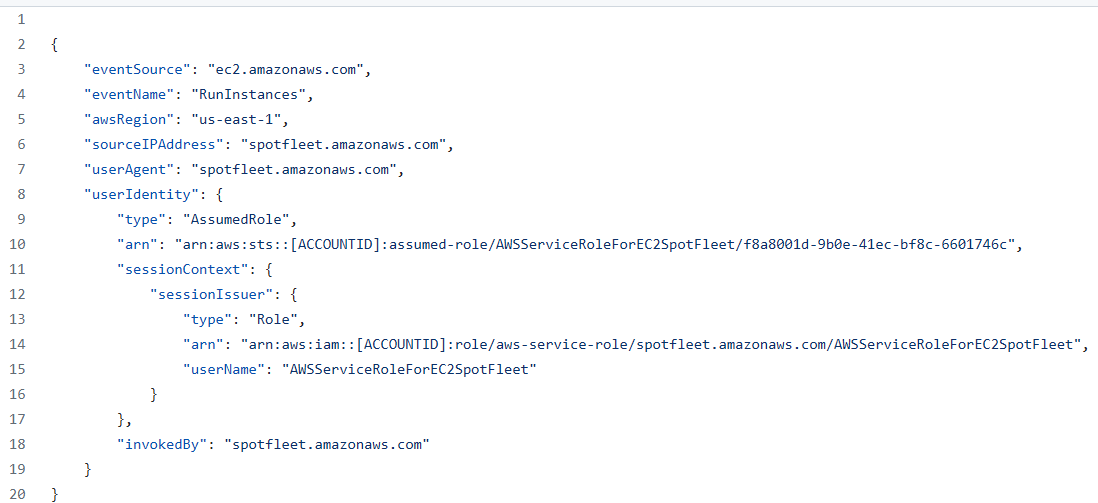

In either case, the service assumes the role directly and performs actions in a session of that role. This makes searching for activity in logs straightforward since the logged principal will be the service’s role session ARN (userIdentity.arn in the below example).

One advantage of service roles over service-linked roles is that service roles are modifiable by the customer. This allows the customer to further restrict the actions the service can take within their account. For example, if a service is expected to create an EC2 instance in the customer account via a service role, the customer can attach a permission boundary and/or additional role policy to the service role to restrict the properties of EC2 instances it deploys (e.g. setting an ImageType condition key). This helps mitigate confused deputy related concerns (see below).

Batch service role with permission boundary set by user

When a customer configures a service to use a service/service-linked role, they are required to have the iam:PassRole permission. This permission gives a principal the ability to grant roles to other principals and, as such, should be treated as extremely sensitive (Refer to our previous post about abusing iam:PassRole for privilege escalation).

Confused Deputies

Confused deputy attacks are a class of attacks where an attacker induces another principal (the “confused” deputy) to act on the attacker’s behalf, allowing the attacker to leverage the privileges of that principal to carry out their desired activity. Confused deputies within the context of AWS typically manifest when dealing with AWS services performing actions within customer accounts or when interacting with customer resources that have assigned IAM roles (e.g. EC2 instance profiles, Lambda execution roles, etc).

A notable component of service-related roles is that because they function as standard IAM roles, they use a traditional trust policy to define the principals allowed to assume the role. The defined principal in a service-related role is the service identifier. For example, EC2’s Spot Fleet identifier is “spotfleet.amazonaws.com”.

Example trust policy for EC2 Spot Fleet

All service-related roles across customer accounts use this same identifier for a service in their trust policies. The same holds true for resource-based policies like S3 bucket policies.

S3 bucket policy allowing CloudTrail write access

Confused deputies are easy to create due to this behavior. By allowing the service access to a role/resource, any customer account can induce the service via their account to interact with another customer account that has an overly permissive policy.

Consider the following scenario using CloudFront and S3:

- An administrator configures an S3 bucket with static web content

- The administrator configures a bucket policy allowing CloudFront to read the bucket contents using the following policy:

S3 bucket policy allowing CloudFront read access

- The administrator configures a CloudFront distribution with the origin set to the bucket, which allows access to the contents via the distribution

- Example: Requesting

https://<distribution>/<file>returns the content of<file>in the bucket

- Example: Requesting

- An attacker configures their own CloudFront distribution that also has an origin set as the bucket

- The attacker requests bucket contents through their new distribution. Since CloudFront is allowed read access to the bucket, the attacker can read the contents

AWS best practices dictate that customers should make use of IAM conditions to restrict access by services to requests originating from that customer’s account and/or other trusted accounts. For general use, aws:SourceArn, aws:SourceAccount, aws:SourceOrgID, and aws:SourceOrgPaths are the relevant global condition keys. In the above CloudFront example, you can use the aws:SourceArn key to restrict access to specific distributions. Some services prefer their own service-specific condition keys for restricting service-based access, such as KMS’ kms:CallerAccount and kms:ViaService.

Service-linked role trust policies cannot make use of these condition keys as customers are not able to edit them. A mitigating factor though is that the iam:PassRole permission, which is required for services to use a service-linked role, cannot be used to pass roles housed in other accounts. This means an attacker cannot attempt to pass a service-linked role housed in a victim account to a service in their account, even if that role’s trust policy would allow it.

User Impersonation

AWS services can also impersonate the calling principal. The mechanism for doing so is referred to as a “forward access session” (“FAS”). Essentially, AWS uses the calling principal’s credentials to generate a new, time-limited copy that it passes to the service. The service then uses these new credentials to act on behalf of the calling principal. In doing so, it inherits the permissions of the calling principal. Any restrictions placed on the calling principal also apply to the service. AWS detailed this internal process during a re:Invent talk in 2021: https://youtu.be/4J8REvs7zaY?t=791 (slides).

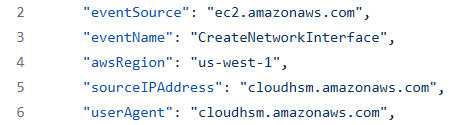

As an example, if you create a CloudHSM cluster, the underlying compute resource receives a network interface in the selected VPC. The CloudHSM service uses a FAS to impersonate the calling principal and create the network interface by calling ec2:CreateNetworkInterface.

From an authorization perspective, impersonation can be a desirable approach as it does not require any additional configuration by administrators. Additionally, its use by AWS services is noted as being restricted to only instances where a user principal first initiates an action:

“FAS requests are only made to AWS services on behalf of an IAM principal after a service has received a request that requires interactions with other AWS services or resources to complete.” (AWS)

However, from an auditing perspective, impersonation has the potential to cause issues with respect to the provenance of activities. Fortunately, within AWS, impersonated actions are denoted as such in CloudTrail logs via the “invokedBy” field.

Fully internal

In some rarer cases, AWS will perform an action on behalf of a calling principal without impersonating that user. The action will be performed wholly internally within AWS, bypassing both logging via CloudTrail and authorization checks that might apply to the caller. An example API call that behaves in this manner is ec2:CreateImage, the API call used for creating an EC2 AMI from an instance. When the ec2:CreateImage API is called, EC2 will power off the instance, take a snapshot of its volumes, create the AMI, then power back on the instance (detailed: here). Since all actions are performed as part of the original ec2:CreateImage call, IAM only checks that the user is authorized to perform ec2:CreateImage, not that they are authorized to perform actions like ec2:CreateSnapshot. In fact, assuming the user only has the ec2:CreateImage permission, their API call will succeed. This allows for an authorization bypass as the caller can create a resource (volume snapshot) without explicit authorization. Even an SCP preventing snapshot creation cannot prevent this action by the user. Furthermore, AWS does not log the intermediate steps of the ec2:CreateImage operation, only the ec2:CreateImage operation. Meaning the snapshot will be created without a log of its creation in the customer’s CloudTrail.

Note: The above issue was deemed to be expected behavior and not a security issue by AWS.

Using some heuristics developed from this example to search through AWS API and Terraform schema information, we attempted to identify other instances of this behavior in a sampling of AWS services. While it is not widespread, it does appear in a few other locations, such as:

- Resources created by EC2 instance creation (

ec2:RunInstances), such as network interfaces - Resources created by default VPC create (

ec2:CreateDefaultVPC), such as subnets - RDS subnet groups created by

rds:CreateDBCluster

Implicit actions like these present an issue as they break the expected behaviors of established controls. If both authorization and auditing controls cannot be trusted, then administrators are restricted in their ability to secure their environments. Ultimately, if administrators wish to identify implicitly created resources, they will need to compare all logged activities against all deployed resources to identify discrepancies between the two. This would also require a mapping between the API actions and the resource they are expected to produce. A more feasible approach is to be mindful of implicit actions when developing policies, treating the API with an implicit action as equivalent to implicit action. Responsibility for documenting these API quirks ultimately falls to AWS.

API Equivalence

Service roles, service-linked roles, and implicit actions all present additional areas of interest for traditional privilege escalation paths. With privilege escalation pathfinding, an attacker aims to be able to navigate from one node to another node until they reach an end node with their desired permissions. Scenarios that allow for confused deputies allow an attacker to expand their pathfinding to any node reachable by a deputy they can influence. With AWS, an example of this would be an attacker that can login to an EC2 instance assigned an overly permissive role. Any action achievable by the EC2’s role is also achievable by the attacker.

Using an EC2 for privilege escalation

As service roles and service-linked roles use their own permissions separate from the principal that initiates the action, it presents an opportunity for permissions arbitrage. An attacker without the ability to perform a desired action can identify service-related roles that can perform such actions then induce them to do so by calling the relevant APIs.

“When setting the PassRole permission, you should make sure that a user doesn’t pass a role where the role has more permissions than you want the user to have. For example, Alice might not be allowed to perform any Amazon S3 actions. If Alice could pass a role to a service that allows Amazon S3 actions, the service could perform Amazon S3 actions on behalf of Alice when executing the job.” (AWS)

Fortunately, the impact of such cases is somewhat limited as the attacker typically has minimal control over the properties of the API calls made by the service.

Implicit actions further attacker pathfinding by introducing an idea of equivalence in API operations. In the above example of ec2:CreateImage, assume an attacker wishes to exfiltrate an EC2 snapshot by marking it as public via the ec2:ModifySnapshotAttribute API but only has the ec2:CreateImage permissions. With a traditional pathfinding approach, they might look for a path following the pattern:

Without the requisite permissions of ec2:CreateSnapshot, the attacker would fail to find an appropriate path, assuming a snapshot of the volume they’re targeting does not already exist.

But if you revise the pathfinding to account for ec2:CreateImage implicitly calling ec2:CreateSnapshot they can expand their searching for patterns like:

This path would match their existing permissions and allow them to achieve their goal of exfiltration. With this form of expansion to traditional pathfinding, attackers can potentially increase their viable paths manifold.

Closing

In this post we covered the mechanism by which AWS services interact with resources in customer accounts and the implications of those mechanisms for authorization and auditing. As always, having a strong understanding of these fundamental concepts will help administrators properly secure their environments.

If you have any questions or concerns, feel free to reach out to me at @2xxeformyshirt.