When we perform purple team engagements, we identify high priority TTPs (tactics, techniques, and procedures) that attackers are using against organizations and execute them in a controlled manner with our clients. In doing so, we often identify common gaps and risky configurations that are widespread across companies (hence why adversaries are performing these attacks so much- they work).

Throughout this process, over time, we notice a detection or preventative control that we talk about so much with our clients that they’ve taken to referring to them somewhat-affectionately as ‘SRA’s latest crusade’. It occurred to me recently that perhaps we should be taking these crusades to a wider audience instead of waiting for the next purple team with our clients. Hence, the Purple PSA is born.

PSA: BLOCK DEVICE CODE FLOW

What is device code flow?

Authentication to Entra ID is performed with tokens. With OAuth 2.0, there are many different authentication flows to grant tokens that we can use to authenticate. One of them, Device Code Flow, allows us to authenticate in order to authorize devices that might not have a great (or any) way to input text. Most of us use equivalent authentication flows on our smart TVs to log into streaming services. To log in, you can either stumble through typing in your email and password with your TV remote (and attempt to lower your blood pressure when you type the password wrong and have to start over), or you can use the handy QR code or link to authenticate your TV on your phone. It’s super useful and convenient, right?

As much as this authentication method has a time and place, Microsoft refers to device code flow as ‘high-risk’ and even “recommends blocking/restricting device code flow wherever possible”. Why? Because it might be leaving your organization vulnerable to one of the most persuasive and impactful social engineering attacks I’ve seen in my career – device code phishing.

The Red Teamer’s side

Adversaries are device code phishing. My team and I are device code phishing. Yes, me. The person begging you to block it. If you have device code flow allowed for all of your users, I’m using it to compromise one of them and gain access to your environment, (sorry, but you paid me to do it). Let me explain…

While I live and breathe the world of purple teams now, my background, and part of my time to this day, is offensive security. If myself or my team is tasked with vishing calls, red teams, or really any offsec assessment where social engineering is in scope, there’s a chance we’ll evaluate if device code flow is enabled, and if so, exploit it.

Here’s an example scenario of what it looks like (and why it’s so effective):

Through OSINT, my team has collected a list of valid employees, their phone numbers, and even your Help Desk phone number. We’ll spoof your Help Desk number and call an employee. We’ll let them know we’re seeing an error for their device, maybe even ask them if they’re having any issues with their M365 applications. Then, we’ll ask them to please visit https://microsoft.com/devicelogin and enter the code we provide them.

While we work tirelessly to train users not to fall for phishing, this type of social engineering slips right by what we coach users to look for:

- It’s Microsoft.com, a site they trust.

- They’re accessing it themselves, and no one has remote control of the screen or is watching via screen share.

- They’re not providing anyone with any sensitive information. They did not share their username, password, or MFA information.

To try to prevent device code phishing, Microsoft added a disclaimer to the portal, though we find that a busy user tends to miss it, or simply trusts us enough to continue:

A side-by-side view of the phish. The left is what the user sees, and the right is what the attacker sees.

And so, the user enters the code onto their workstation and authenticates via SSO. We hang up the phone, and the user is none the wiser.

Once the user inputs the code, they go through a typical SSO authentication flow.

In the background, the attacker (us) has just obtained the user’s tokens. By default, that token is valid for 60 minutes. You might think that means an attacker has 60 minutes to try to establish a persistent foothold in the environment, think again. The real kicker is the refresh token the attacker gets, which allows them to obtain a fresh access token. By default, refresh tokens are valid for 90 days.

Yes, you read that right – the attacker now has access to your environment for 90 days. And since the user completed the authentication themselves, the attacker doesn’t need MFA.

A view of the attacker receiving the user’s tokens (right) after they authenticate (left). The FOCI (or Family of Client ID’s) tells us which applications the refresh token is valid for.

I linked several tools below that you can use to test this out for yourself. The above screenshots use TokenTacticsv2:

Import-Module .\TokenTactics.psd1

Get-AzureToken -Client MSGraph

Caveat – I’m oversimplifying these tokens a bit. Access tokens only have access to the Microsoft endpoint they are requested for (e.g., Microsoft Graph). Refresh tokens can be used to request access tokens for a larger group of applications (depending on the original application – see the FOCI highlighted above), or sometimes to request a Primary Refresh Token. In a lot of real-world attack scenarios, an adversary will use this phish to access applications like the user’s OneDrive, SharePoint, Outlook, Teams, etc. and try to further their access from there (example real-world scenario: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2025/02/13/storm-2372-conducts-device-code-phishing-campaign/). Others have done a better deep dive on this than I could dream of doing. Peruse the “red team” references below, if you’re interested, but I’m going to keep it simple – This. Is. Bad.

The Blue Teamer’s Side

Now that I’ve sufficiently scared you (step 1 of SRA’s latest crusade), let’s talk about how to stop anyone from doing this to your organization.

I’ll start with the most direct and the least headache to implement: Block Device Code Flow with a Conditional Access Policy (CAP).

As we discussed, device code flow exists for a reason, and it has its helpful use cases. First let’s see where, if anywhere, device code flow is being used in your organization:

SigninLogs

| where TimeGenerated > ago(90d)

| where AuthenticationProtocol == "deviceCode"

| summarize by AppDisplayName, UserId, UserPrincipalName

According to our clients, it’s typically not in use much, or at all, but we can make exceptions in our CAP where it’s necessary.

You can also skip this step if you want, because either way we (and Microsoft) recommend configuring policies in report-only mode first to evaluate if there is any impact to putting this baby in prod.

Configuring a CAP to block device code flow

Scope the correct users to apply this policy to in the “Users” section. Ideally, this is set to all users (with maybe one or two exceptions, such as a break-glass account). You will also need to scope this CAP to the appropriate resources in the “Target resources” section. Again, ideally you can select All resources. Under Conditions > Authentication flows toggle Configure to Yes. Under Transfer methods select Device code flow, and under Grant, select Block access.

Once you are as confident as you can be that your policy is tuned and ready to rock, set Enable policy to On.

Starting in February 2025, Microsoft will begin rolling out policies which limit device code flow by default! You may have this already in report-only mode and only need to switch it to On after evaluating if there is any impact.

Here’s Option #2 (Part of our purple philosophy is catering our recommendations to what works best for your organization.):

A Conditional Access Policy which requires authentication to come from a compliant or managed device blocks most device code phishing scenarios. If the attacker does not have a compliant or managed device, the authentication will ultimately fail.

As more and more initial access attack vectors against Entra ID are released, we find time and time again that the best defense is often requiring access to come from managed devices. This might not work if your organization has people who travel without their laptops, work in the field, or generally need to be able to authenticate (to say, check their email) from everywhere.

To configure a CAP to require authentication from compliant devices, scope it appropriately first, including adding any Conditions such as applicable Device platforms. Under Access Controls, select Require Device to be marked as compliant.

Don’t forget to put this one in Report Only Mode first and prepare yourself to get an earful from some unhappy users.

Configuring a CAP to require compliant devices

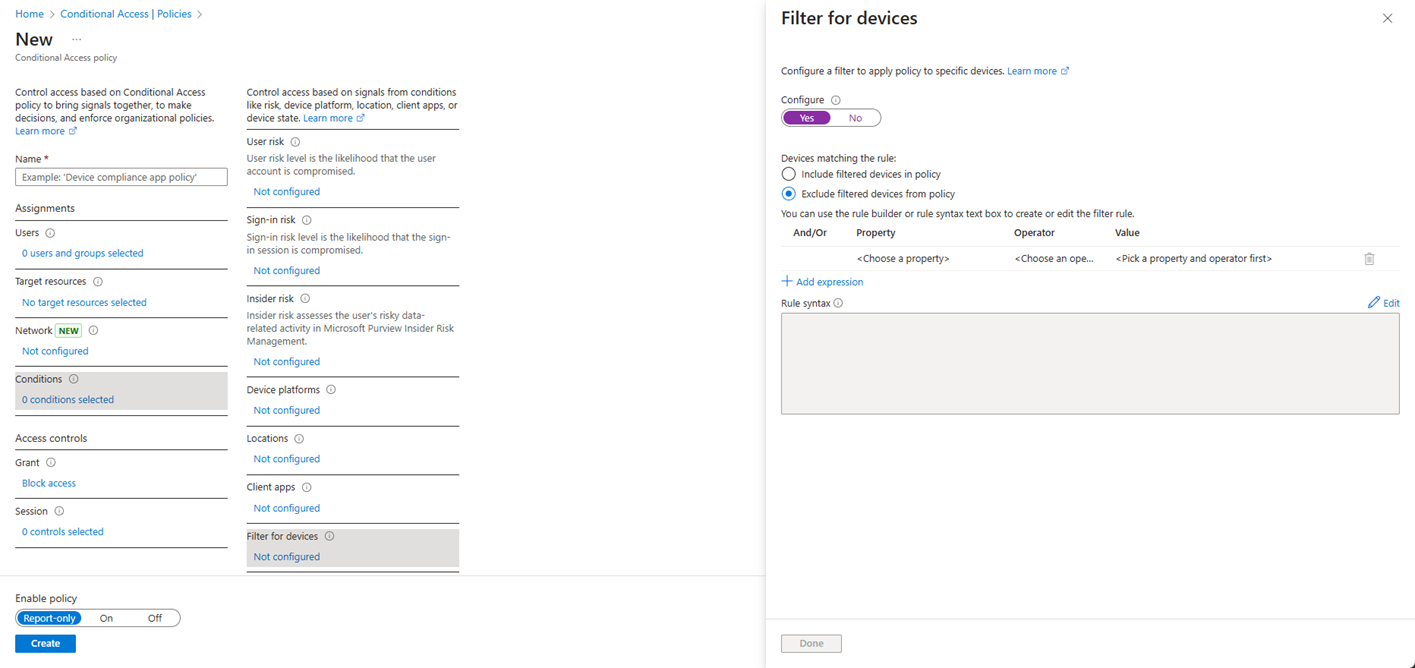

Alternatively, you can also create a CAP which requires authentication from a managed or hybrid-joined device. Create a policy which blocks all access, excluding devices you specify (you will need to add a rule for filtered devices).

Configuring a CAP to block access except for filtered devices

Example device filter for registered or joined devices:

(device.isCompliant -eq True) -or

((device.operatingSystem -startsWith "Windows") -and (device.deviceOwnership -eq "Company") -and (device.trustType -eq "AzureAD")) -or

((device.operatingSystem -startsWith "MacOs" -or device.operatingSystem -startsWith "OSX") -and (device.deviceOwnership -eq "Company") -and (device.trustType -eq "Workplace")) -or

((device.operatingSystem -startsWith "iOS") -and (device.deviceOwnership -eq "Company" -or device.deviceOwnership -eq "Personal") -and (device.trustType -eq "Workplace")) -or

((device.operatingSystem -startsWith "Android") -and (device.deviceOwnership -eq "Company" -or device.deviceOwnership -eq "Personal") -and (device.trustType -eq "Workplace"))

Note: Attackers can potentially bypass this control if they can register or join devices to your tenant. By default, a standard user can enroll up to 15 devices to Intune or register 50 devices in Entra ID. To avoid a tangent, I’ll just link this here and suggest you review these settings (and your requirements for device compliance) before getting the warm-and-fuzzies from this CAP https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/entra/identity/devices/manage-device-identities.

A brief word on protecting the tokens themselves:

We can shorten the lifetime of access tokens to as low as 10 minutes (remember, the default is 60 minutes). I won’t pretend to offer a specific recommendation here- it is a dance between system performance, user experience, and security (what isn’t?). However, these tokens cannot be revoked (except with the use of Continuous access evaluation). If we imagine the user realizes they were phished and changes their password, we revoke all refresh tokens, etc. the attacker will still have 60 minutes on the clock with access to the application their access token is for.

We cannot shorten the lifetime of refresh tokens from 90 days, which negates some of the security benefits of shortening the access token lifetime- we can use the refresh token to *simply* get a new access token. However, refresh tokens can be revoked. Keep this handy reference table in mind to be sure refresh tokens were properly revoked by any change you make (it’s in less scenarios than we might expect) https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/entra/identity-platform/refresh-tokens#token-revocation.

Note: There are a million caveats, exceptions, headaches, etc. associated with the above commentary on tokens. For more information on how you can implement additional security measures for tokens, I have attached references regarding Token protection and Continuous access evaluation. Again, we’re avoiding a tangent here.

The Purple Teamer’s PSA

In conclusion, BLOCK DEVICE CODE FLOW.

References:

My team (red and blue), especially Brian Zick, for Conditional Access Policy implementation, and Evan Perotti for insight into advanced protection on Microsoft tokens.

For my blue teamers:

- https://techcommunity.microsoft.com/blog/microsoft-entra-blog/new-microsoft-managed-policies-to-raise-your-identity-security-posture/4286758

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/entra/identity/conditional-access/policy-block-authentication-flows

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/entra/identity-platform/v2-oauth2-device-code

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/entra/identity/conditional-access/concept-authentication-flows

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/entra/identity-platform/refresh-tokens

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/entra/identity-platform/configurable-token-lifetimes

- https://mobile-jon.com/2024/09/09/the-magnificent-8-conditional-access-policies-of-microsoft-entra/

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/entra/identity/conditional-access/concept-continuous-access-evaluation

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/entra/identity/conditional-access/concept-token-protection

For my red teamers:

Sarah Hume

Sarah leads purple team service delivery at SRA. She specializes in purple teams, internal network penetration testing, and physical security intrusion and assessments.

Sarah also has experience in external network penetration testing, web application assessments, OSINT, phishing/vishing campaigns, vulnerability management, and cloud assessments.

Sarah graduated Summa Cum Laude from Penn State with a B.S. in Cybersecurity. She is a Certified Red Team Operator, Google Digital Cloud Leader, AWS Certified Cloud Practitioner, and Advanced Infrastructure Hacking Certified.